Researchers working in the field of psychotherapy have, for more than 50 years, attempted to document what are known as significant moments of change during which a client’s attitudes and behaviors undergo transformation.[i] Financial counseling and planning and planning, as a sister profession to psychotherapy and the mental health field, has adopted many of the insights gleamed from these studies. Consider the acceptance of therapeutic interventions and models. Today, it is common for financial advisors to conceptualize the manner in which someone is willing to change behavior as a process. This process is best conceptualized in the transtheoretical model of change, in which people move through five stages starting with precontemplation and ending with behavioral maintenance.[ii] The adoption of cognitive-behavioral interventions is another example of the way financial counseling and planning and planning, as an emerging profession, has adapted clinically validated approaches used in the mental health field to the purposes of helping people better manage their household financial situation.

Interestingly, however, it has only been within the last decade that financial advisors have taken an interest in the way the planning environment may impact client outcomes. Some of the earliest work dealing with this topic was published by Sonya Britt and John Grable.[iii] They showed that the physiological response of clients undergoing financial counseling and planning and planning was significantly influenced by the physical environment where the client and advisor met. More specifically, Britt and Grable noted that financial advisors who use a therapeutic office setup (i.e., one with flexible seating), as compared to a more traditional financial planning arrangement (i.e., the use of desk), are able to solicit more information from clients, while at the same time reducing client stress.

The acknowledgement by financial advisors that the planning environment likely does have a potentially large impact in shaping a client’s willingness to change attitudes and behaviors creates an important practice management question: How should an office environment be structured to positively affect clients psychologically, emotionally, and physically? The following discussion highlights findings from the literature that provide insights into answering this important question.

The Office Environment: A Reflection of the Advisor

Financial advisors are rarely taught about ways to utilize their office environment as a tool to manage the financial planning process. Nearly all financial education focuses on the nuts-and-bolts of specific financial interventions or on the process of counseling and planning and planning, with an emphasis on communication and counseling and planning and planning theory. While these are obviously at the root of any successful financial advisory practice, it is important to note that an advisor’s office environment also plays an important role in shaping the experiences of clients.

The importance of the office environment is universal. This means that a financial advisor should spend time to create an environment that facilitates client financial health, regardless if the advisor is working out of their home, has a small office in a suburban center, or owns a suite of offices in a large building.

A financial advisor’s office environment consists of three dimensions:[iv] (a) physical, (b) mental, and (c) emotional. The physical dimension includes things such as how warm a room is and how light or dark the lights are during a session. The mental dimension includes the messages sent by an advisor to a client. Messages can be conveyed through pictures and personal objects in a room. The emotional dimension includes the elements in the environment that shape the way clients feel, including the use of colors and textures.

A financial advisor’s office communicates cues of safety, comfort, diligence, and competence. Eight elements constitute the counseling and planning and planning environment:[v] (a) office accessories, (b) color, (c) design and furniture, (d) lighting, (e) smell, (f) sound, (g) texture, and (h) temperature. According to Levitt and her associates,[vi] an advisor’s office environment is a projection of the person providing the service. As such, taking care when choosing the objects in meeting rooms, the comfort of meeting areas, and even the sights and sounds heard during sessions become important elements that should be controlled during the financial counseling and planning and planning process. A description of the most important environmental elements is presented below.

Environmental Accessories

Environmental accessories include things such as live plants, artwork, and personal objects (e.g., family photographs and mementos). If used appropriately, accessories relay meaning and the personality of the advisor to clients. There is a downside to the use of accessories as well. These elements generally require upkeep in terms of dusting, maintenance, and with plants, watering. The following are important takeaways when thinking about accessories in the counseling and planning and planning environment:

First, the financial advisor should choose accessories that appeal to the advisor. It is important for the advisor to take ownership of the environment because those who are “unhappy in their environments may inadvertently exhibit less positive attitudes and behaviors toward clients, and their judgments may be tainted by their dissatisfaction.”[vii]

Second, when maintenance can be ensured, the office environment should include live green plants. Plants represent renewed life and growth. Many clients also find plants soothing.[viii]

Third, advisor offices should include artwork. The consensus is that hung pictures should be texturally complex, representing natural scenes. Financial advisory clients typically find abstract art, urban scenes, and pictures of people to be stressful.

Fourth, cues of status and credibility should be used whenever possible. Clients often need reassurance that the person they are working with is competent. One way to signal competency is to display credentials, such as diplomas and certifications, in direct sight of clients.

Environmental Color

The choice and use of colors in the advisory environment can often lead to unexpected outcomes. In general, people respond positively to light colors and negatively to dark colors. However, responses can be skewed by the age and gender of a client. For example, young men report liking greens and browns, whereas young women prefer yellows and purples.[ix] Older women also like purples and grey to black hues. Older men have a dampened response to these colors. Physiologically, red and orange colors tend to increase blood pressure, pulse, and respiration. It is not surprising that fast food chains use these colors to speed up the time customers spend in restaurants. These colors should be avoided in most advisory environments. Instead, if color is to be used, blues and violets should be considered because these colors have been shown to reduce blood pressure and physiological reactions;[x] however, others have reported that blue-violet combinations prompt sadness and fatigue among clients.[xi]

As this summary indicates, the choice of colors for an office environment can be complex. Given that financial counseling and planning and planning appeals to older (not youths) males and females, and often couples, the following recommendations are presented as guidelines for choosing office colors:

First, the color chosen should match what the financial advisor finds pleasing. After all, the financial advisor will be working in the office environment daily, and as such, the color should be pleasing to the advisor and staff.

Second, the use of neutral wall colors is a good choice (e.g., off white, beige, light gray) for most environments. Color can then be added back to the room with art, plants, and furniture.

Third, if and when a non-neutral color is selected, blues and violets should be chosen over bright arousing colors.

Environmental Design and Furniture

The design of a room and the furniture in the room define a client’s ability to move around spatially. Furniture also creates visible and implied barriers and boundaries.[xii] For example, a chair without armrests can make a client feel vulnerable because they may feel that they have no personal space. Also, a desk in a room may signal a power relationship with the advisor “being in charge” and the client being in a weaker position.

Much of the research involving environmental design and furniture use has revolved around the concept of individual body buffer zones or what is known as interaction distances.[xiii] Everyone has an interaction preference, which is the distance between two or more people that should exist before discomfort sets in. Among US financial advisory clients, this distance is between 48 and 60 inches. Gender and cultural differences have an impact on these benchmarks. For instance, women are more comfortable with smaller buffer zones, whereas men prefer a larger interaction distance. When a client and financial advisor are of the opposite sex, clients tend to prefer a wider buffer zone. It is important to note that clients from what are known as ‘contact cultures’ (e.g., those from South America and France) often prefer a small buffer zone.

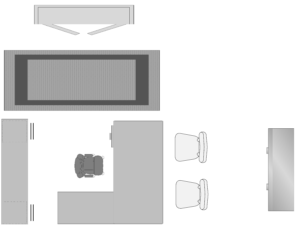

Having a rudimentary understanding of buffer zones is important when choosing how an office, where client meetings are held, is arranged. Office space can be described as either traditional or therapeutic. Figure 1 illustrates a traditional office environment. In Figure 1, the financial advisor sits behind a desk with the client sitting on the other side of the desk. This office environment facilitates the sharing of paper and provides a zone of familiarity for the client.

Figure 1. Traditional Financial Advisor Office Space

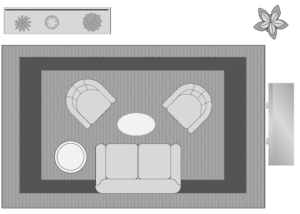

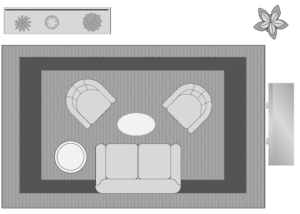

A therapeutic office environment is shown in Figure 2. In this office, the desk has been replaced with a small table that can be used to layout paper work and sign documents, if needed. The emphasis in the space, however, is the couch for the client and the chair for the advisor. This environment facilitates discussion and sharing of ideas.

Figure 2. Therapeutic Financial Advisors Office Space

Although nearly all financial advisors prefer an environment like that shown in Figure 1, clients generally find the space shown in Figure 2 to be preferable. Essentially, the desk in Figure 1 represents, figuratively and practically, a barrier between the client and advisor. Clients find advisors to be more accessible and friendly when the ‘barrier’ is eliminated. Interestingly, research suggests that clients do not find the use or lack of a desk to impact advisor credibility,[xiv] although women advisors are sometimes perceived as more competent when using a desk. Perceptions of competency for male advisors, on the other hand, have been reported to be higher in therapeutic office environments.[xv]

The following points highlight the research on environmental design and furniture use:

- First, the placement of office furniture should follow the needs of clients. If the intent of a financial advisor’s practice is to create a trusted relationship with clients as a means to change attitudes and behaviors over time, then a therapeutic office environment should be considered (Figure 2). If, on the other hand, a financial advisor’s primary objective is to facilitate a limited number of client outcomes in a short period of time (e.g., creation of a budget or the establishment of a debt repayment plan) then a traditional office space is likely more appropriate.

- Second, instead of purchasing heavy difficult to move furniture, a financial advisor should consider using movable chairs and small tables for writing and sharing information. Additionally, it is important to provide clients with seating alternatives, such as a simple chair or a love seat/couch. This approach allows a client to establish their preferred buffer zone. If advisory services continue over several sessions, it is likely that the financial advisor will find that the interaction distance selected by the client will shrink over time. For example, at the first meeting the client may choose to sit at the end of a couch with the advisor in a chair several feet away. By the third or fourth meeting the client may purposely sit closer to the advisor, thus reducing the buffer zone and increasing disclosure and generating a stronger working alliance.

- Third, it goes without saying, but the office environment where clients are met should always be clean and neat. A dirty office signals sloppiness.

Lighting

Environmental lighting helps create client impressions about a financial advisor’s practice. Lighting is known to shape perceptions of spaciousness, privacy, and competence.[xvi] In general, the literature suggests that financial advisors should employ full-spectrum lighting in combination with natural lighting when possible. The strict use of florescent lighting, for example, should be avoided because this source of light tends to create a washed out environment that clients sometimes associate with uncomfortable clinical settings. The more natural light the better. Natural light reduces depressive symptoms and facilitates open dialog. It is important to remember, however, that client seating should always be situated so that the client does not face a window. Allowing a client to see outside during an advisory session can result in disengagement and distraction on the part of the client.

Smell

It is not surprising, but the psychotherapy literature clearly indicates that “exposure to specific odors affects various psychological processes such as mood, cognition, person perception, health, sexual behavior, and ingestive functions” (Levitt et al., p. 79). Financial advisors, like mental health professionals, should avoid the use of colognes and perfume. They should also ensure that their breath smells fresh during client meetings and that they do not have body odor. A simple strategy regarding office smells involves purchasing a plug in room deodorizer. Preferred smells include scents of baked foods and fruit fragrances.

Sound

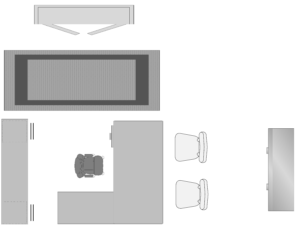

External sounds during counseling and planning sessions are known to reduce advisor task performance and reduce sharing of information on the part of clients. Clients often assume that if they can hear sounds occurring outside of the room in which they are meeting with an advisor, others can hear their discussion. This can trigger an unexpected fracture in client-advisor dialog. This is the reason that nearly all psychotherapists recommend and use a sound masking device when working with clients. Figure 3 shows a typical device that sits on the floor outside of the counseling and planning room. This particular device creates swirling wind sound. Other devices can produce wave sounds and light music, both of which can also be effective in dampening outside noises.

Figure 2. Sound Making Device

Texture

Texture is a concept that touches nearly every aspect of a financial advisor’s office environment. Clients perceive texture through sight and touch. Nearly everything that a client interacts with in a financial advisor’s office (e.g., flooring, furniture, brochures, etc.) has some degree of texture. The general recommendation is that the office environment should be built around soft materials and textured surfaces that absorb sound. Using this approach reduces the ‘clinical’ feel of an office space and creates a more inviting environment.

Temperature

The final element associated with the physical office environment involves the temperature of the office and the space where the advisor and client meet. Issues to consider include placement of seating in relation to air vents and sources of heat, cold, and drafts (e.g., doors and windows). Generally, people prefer rooms that have an average ambient temperature between 69 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit, with 30 to 60 percent humidity.[xvii] Rather than allow a client to set the temperature, the financial advisor should set a comfortable temperature and make periodical changes throughout the day or as requested by a client.

Summary

As this discussion has highlighted, the environmental space in which a financial advisor works can play an important role in shaping client attitudes and behaviors. This is true across financial counseling and planning methodologies—the single office practitioner to the multi-staff counseling and planning practice. The office environment is something that all financial advisors should work to manage in ways that prompt client sharing of information and implementation of recommendations. While there is no “one best” approach for all financial advisors, the following are general guidelines that can be used by financial advisors when thinking about ways to optimize an environmental space:

- The financial advisor (or firm) should create an office space that appeals first and foremost to the advisor (staff advisors).

- Office spaces should convey a message of who the advisor is as an individual and professional though the use of plants, art, mementos, and certifications.

- When art is used, it should be texturally complex but not abstract.

- Given the diverse reactions to color, a neutral color scheme should be used with splashes of color added via furnishing and objects.

- For those interested in reducing stress among clients, blues and violets can be used in room designs.

- The use of a therapeutic office space should be considered for those wishing to enhance client communication, increase client disclosure, and promote a strong client-advisor working alliance. At a minimum, office furniture should be flexible and movable in a way that allows clients to choose the seating arrangement that best matches their buffer zone.

- Attention should be paid to the use of light, sound, smell, texture, and temperature. Natural light is the best option, if available, followed by full-spectrum lighting. Effort should be taken to mask outside sounds and annoyances. It goes without saying, but obnoxious smells should be avoided and controlled. The overall counseling and planning environment should be one that communicates professionalism and privacy. This can be accomplished by using soft sound deadening materials. Finally, financial advisors should monitor the temperature of their office environment to ensure that the air temperature and humidity are appropriate.

Note: The information in this blog is copyrighted (John E. Grable, 2017(C).

For more information about ways the research happening in the Financial Planning Performance Lab contact Dr. John Grable: grable@uga.edu

References

[i] Levitt, H., Butler, M., & Hill, T. (2006). What clients find helpful in psychotherapy: Developing principles for facilitating moment-to-moment change. Journal of Counseling and planning Psychology, 53, 314-324.

[ii] Prochaska, J. 0., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change: Application to the addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47, 1102-1114.

[iii] Britt, S., & Grable, J. (2012). Your office may be a stressor: Understand how the physical environment of your office affects financial counseling and planning clients. The Standard, 30(2), 5 & 13.

[iv] Venolia, C. (1988). Healing environments. Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts.

[v] Pressly, P. K., & Heesacker, M. (2001). The physical environment and counseling and planning: A review of theory and research. Journal of Counseling and planning and Development: JCD, 79, 148-160.

[vi] See Levitt et al. (2006).

[vii] See page 150 of Pressly and Heesacker (2001).

[viii] Carplman, J. R., & Grant, M. A. (1993). Design that cares: Planning health facilities for patients and visitors (2nd ed.). Chicago: American Hospital Publishing.

[ix] Hemphill, M. (1996). A note on adults’ color-emotion associations. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 157, 275-278.

[x] Kwallek, N., Woodson, H., Lewis, C. M., & Sales, C. (1997). Impact of three interior color schemes on worker mood and performance relative to individual environmental sensitivity. Color Research and Application, 22, 121-132.

[xi] Levey, B. I. (1984). Research into the psychological meaning of color. American Journal of Art Therapy, 23, 58-62.

[xii] Ching, F. (1987). Interior design illustrated. New York: Nostrand Reinhold.

[xiii] Hall, E. T. (1969). The hidden dimension. New York: Anchor Books.

[xiv] Amira, S., & Abramowitz, S. I. (1979). Therapeutic attraction as a function of therapist attire and office furnishings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47, 198-200.

[xv] Bloom, L. J., Weigel, R. G., & Trautt, G. M. (1977). Therapeutic factors in psychotherapy: Effects of office décor and subject-therapist sex pairing on the perception of credibility. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 45, 867-873.

[xvi] Flynn, J. E. (1992). Architectural interior systems: Lighting, acoustics, and air conditioning. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

[xvii] See Levitt et al. (2006).